Bugatti Type 57S Atlantic Coupe

Words: Kyle Cassidy | Photos: Tiffany Watts / Alex Schultz

Here we tell the tale of a mammoth undertaking to recreate a famous lost Bugatti.

While having one rare and desirable vintage Bugatti might be enough for some, Classics Museum owner Tom Andrews is not your typical collector.

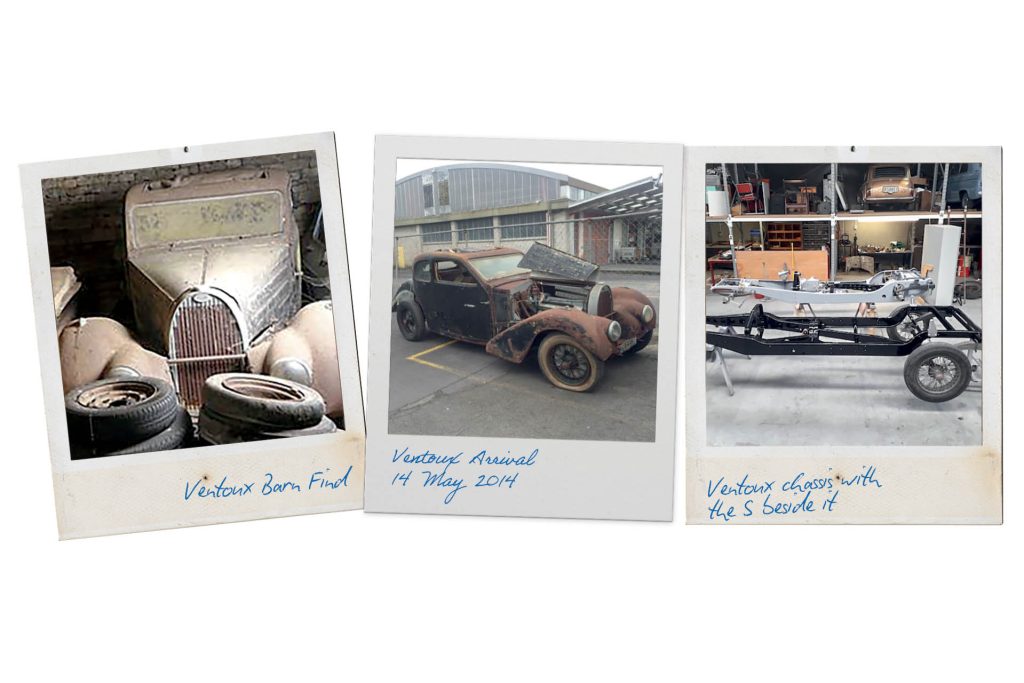

Having purchased a Type 57 Ventoux in Paris in 2015, he was then inspired to recreate a famous Bugatti lost to history. We’re talking about Jean Bugatti’s 1936 Type 57S Atlantic Coupe, dubbed “La Voiture Noire”.

While replicas of the Atlantic Coupe exist, no one had managed to mimic the Black Car. But as you can see from the photos, the team at the Classics Museum has done quite a job.

But first some history

Bugatti rolled out a Type 57S Aerolithe Coupe in 1935, a concept car essentially. Its body was made of a lightweight Elektron alloy, which had a large content of magnesium. Unable to be welded, the panels were riveted together creating the dorsal seam over the roof and along the arches. Jean Bugatti then developed this concept into the production reality; the Atlantic. This used aluminium for ease of manufacturing, but retained those regal riveted seams for good effect. Production began in 1936 but only four would ever be built, each unique.

The Atlantic Coupe rested on a modified Type 57 chassis, one that was shortened and re-engineered to allow the rear axle to pass through the frame, rather than under it, to reduce the ride height. The chassis was subsequently called the 57S; that’s S for “surbaissé” meaning lowered. It also used unique inverted quarter-elliptical leaf springs on the rear. The engine needed a dry-sump lubrication system to allow it to sit lower in the S chassis.

The fabled “La Voiture Noire” was Type 57S Atlantic Coupe No 2, chassis number 57453. This was owned by Jean Bugatti. He was just 27 when he designed the Atlantic in 1936, which was also the same year he was named as head of the company. Just three years later, he would die behind the wheel of a Type 57C, after swerving to avoid a cyclist and crashing. This was the same year the famous Black Car went missing. While various theories exist as to what might have happened to the car, it has never been seen since. Perhaps it is lying somewhere in a shed, waiting to be discovered and crowned the greatest barn find ever. If it’s still around, estimates suggest it would be worth in excess of $US100 million.

The re-birth

The Atlantic recreation was quite some task, given the team from the Classics Museum started quite literally from scratch. Greg McDell heads up the Classics Museum workshop and managed the build of what would be a monumental task.

“Tom started the ball rolling 10 years ago when he bought the Ventoux, but his dream was the Atlantic. I started working for him in 2018 and that’s when he asked me to oversee the build. I was tasked with basically building the car from scratch.”

Tom’s original idea was to use the Ventoux as a basis for constructing the replica, but decided to restore that car back to its original glory.

While the thought of building an Atlantic from scratch while restoring another Bugatti at the same time might have been daunting, Greg said it actually helped the process.

“We had the Ventoux in the workshop, restoring that as we built the Atlantic. Having that revealed the build techniques they used at the time, and told us what we needed to know in order to build the Atlantic properly.”

He said it was absolutely critical to follow period construction techniques as the team wanted to build the car as accurately as possible.

“Initially, 50 per cent of my time was staring at a computer or books or being on the phone, just trying to work out what we needed. It was quite amazing how many bits and pieces exist from very old cars around the world but you have to have the time and patience to source them.”

There isn’t much that can be bought in the way of new parts for a 90-year-old car, especially when only four were ever made. “We could source a few bits like the unique Bugatti bolts new from a place in France, and found a few old genuine Bugatti bits but most of it has been handcrafted here in New Zealand.”

The bones of it

Tom had already got the Atlantic ball rolling before Greg took over the project, having commissioned the build of a timber body frame from Germany in 2016. One of the few parts made in Europe, this was entrusted to Udolahr Von Joerges, a master of recreating Bugatti frames.

It’s thought that around 18 replica Atlantics have been made over the years, most completed by a Danish engineer, Erik Koux. His measurements and templates were taken from the fourth Atlantic Coupe (the Ralph Lauren car) in the mid-70s. And this has dictated the form of most of the replicas since. Von Joerges had access to patterns made by Koux, and so once the timber frame arrived in NZ in 2017, it needed to be modified in certain areas to accurately replicate the No 2 black car.

Greg said this was handled by Gordon White, who works at the museum as well. “He was instrumental in the build. He’s a great engineer and his woodwork skills came in handy. Along with the wood dash and trim, we modified the frame to make sure it was accurate to this car, not just a generic Atlantic.”

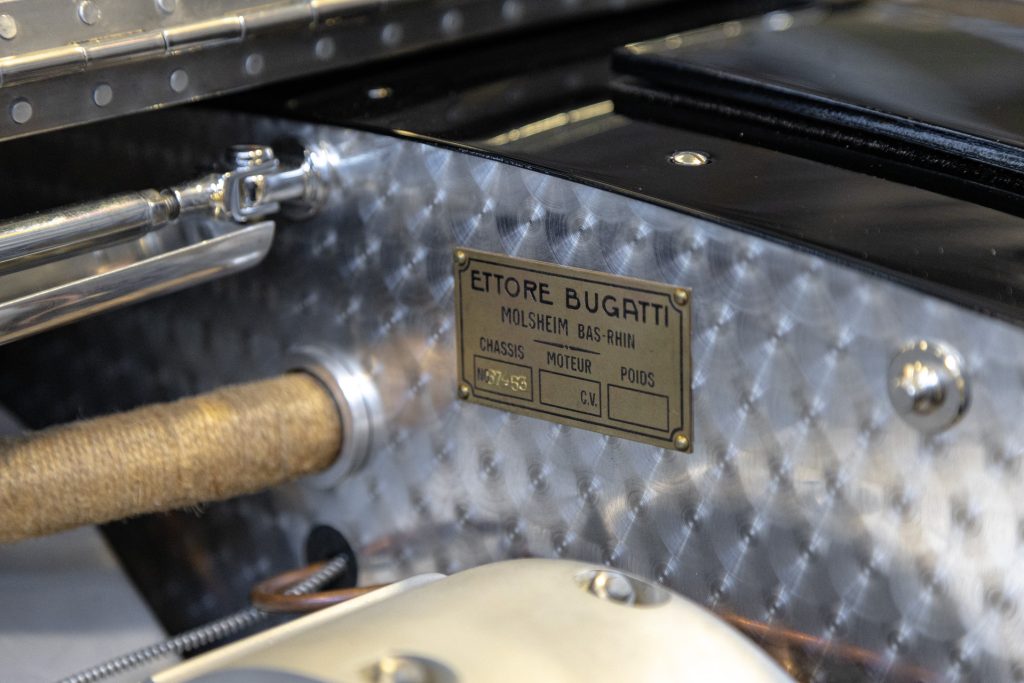

With just 43 Type 57S Bugattis being produced, sourcing an original chassis was an impossibility, so the Classics team had to make one.

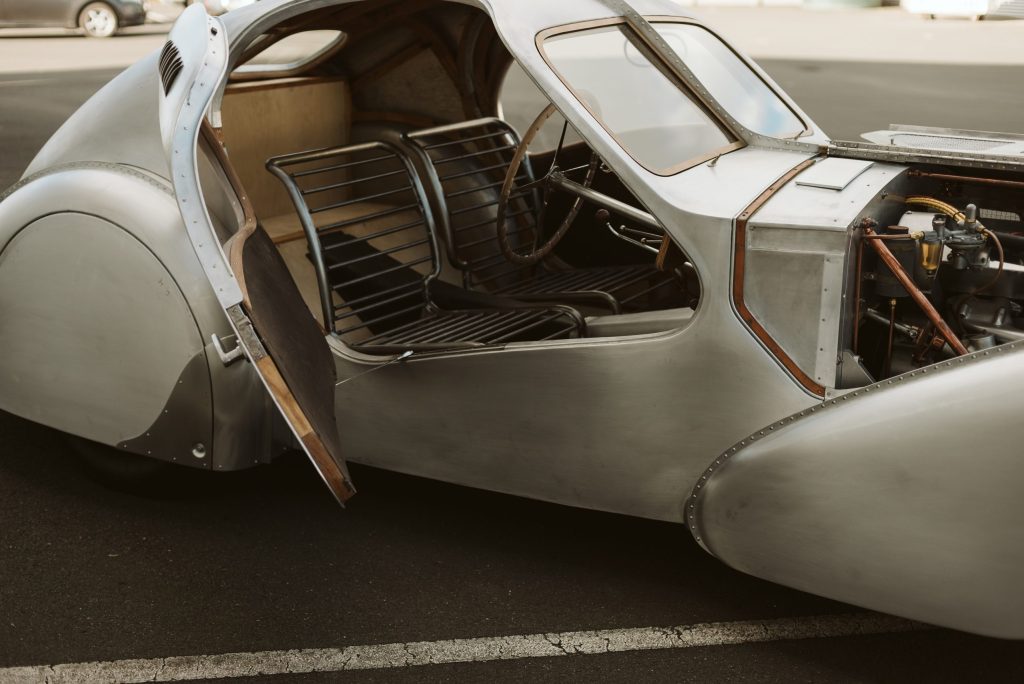

They gained access to original 57S blueprints from the Bugatti Trust and used photos of an S chassis that is displayed in Europe to help ensure accuracy. The team had to press and roll the side rails of the chassis and then cut the axle holes out. The Atlantic’s special front cross member was sourced from France, while the other cross members were pressed in Hamilton and hot riveted in place.

Truly bespoke

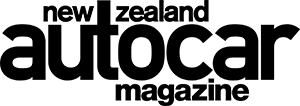

Simon Tippins of Creative Metalworks was entrusted with the alloy panels.

These were formed by hand using a Pullmax machine and lots of care, time and attention. A case in point is the spare wheel well which was formed from one piece of aluminium. Imagine how hard it would be to create a perfect shallow cylinder from one flat sheet of alloy.

“It did take a while to do the body, but we needed to get that right,” says Greg. “The black car is unique in a lot of ways. We were trying to form the body from black and white photos, it was a difficult process as we were basically doing it freehand. But we made sure that every shape was correct for the missing car.”

There are also a few original Bugatti parts used in the build, sourced from around the world. These include the steering box and while the transmission is a Bugatti box, it has a new housing for the original internals. The diff has an Atlantic-specific finned housing, but it has original axle, tubes and internals.

“We needed to outsource some stuff to local engineers and other craftsmen. You can’t do everything yourself, so it was definitely a team effort. There were a few trying episodes along the way, but we managed to get there.”

New leaf springs were made locally while stub axles were machined from a block of steel. The aluminium brake drums were also machined from a solid block. A new set of steering arms was made, as were the hand brake shaft, drive shaft and pedal assembly.

Discovering treasure

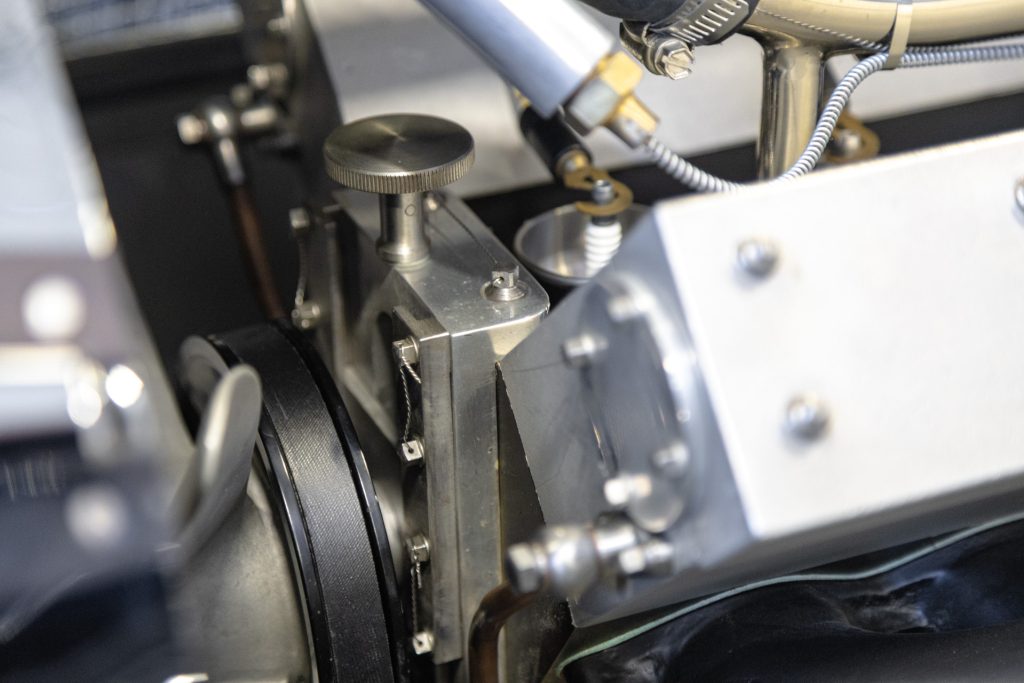

One vital piece that was missing was a suitable straight eight.

“Finding the engine was incredible. I’d contacted museums and collectors all over the world trying to find an original. It got to the point where they just laughed at me. We started negotiations to build an engine from scratch but that’s when one of the workers at Auto Restorations remembered a Bugatti restoration they’d done many years ago, and that there were leftover bits and pieces.”

Introductions were made, and Greg was off to Christchurch.

“It was hard case. I literally walked down the farmer’s race, opened the barn doors, moved the hay bales and dead rats and there was an engine.”

Well, most of an engine. This was purchased and then sent to Auto Restorations to resurrect it. “They had to make a new block for it, new crankshaft, all the conrods, pistons, all the timing gear. And of course, the Atlantic’s dry-sumped, so we had to build the entire dry-sump system. Oil pumps, oil tanks, everything like that.”

The engine was vital because this is not a static replica, it’s an operational recreation.

“It drives beautifully. It really does. And that’s one of the key things that makes this replica different. Some of the more recent replicas made are non-drivers.”

Challenging but rewarding

Greg says building a car from scratch is a completely different animal than a restoration. “The Ventoux was completely rotten but you’ve got most of the answers to all the problems in front of you. However, to start with nothing was a challenge. And the way the Atlantic was built originally was interesting. Bugatti was ahead of its time in design and engineering, but some of the ideas were a bit out the gate. As a challenge, it was great but there were a few long nights here and there.”

The car made its public debut at the recent Art Deco festival in Napier, where Ivan Dutton from Dutton Restorations (renowned UK-based Bugatti restorer) was in attendance.

“We gave him a private viewing of it. He has one of the originals at his workshop, getting some work done. He’s restored over 50 Bugattis, and said in all his years he had never seen a car built to the level of this one. So, that was pretty high praise.”

Greg says they were warned by one of his colleagues that Ivan can be very blunt. “They said if he sees something wrong, he’ll tell you about it. But we had him stumped. It wasn’t until we took him for a drive that he pulled us up on the faulty fuel gauge. But he was even impressed with the way it drove. He says they normally wobble all over the road.”

The build took six and half years, though Greg and his team also restored the Ventoux during that time, along with a few trucks as well!

“Yeah, it was a big job. I didn’t keep an accurate record of the hours, but we sunk at least 16,000 hours into that car.”

One can assume there is a substantial stack of invoices somewhere detailing the build. “I know what the number is but I can’t say. We wanted to build the best replica in the world of that missing car. So it does cost a lot of money to achieve that.”

Are there any plans for it to go anywhere other than around New Zealand? “No, it’s been asked to go to Pebble Beach and to an auto show in France, but it costs a lot of money to transport something like this, and you run the risk of it getting damaged in transit. My theory is, they can all come and pay 20 bucks to see it here at the museum.”