Auckland to Wellington in a Tesla Model 3 FSD-S Review

Words/Photos: Richard Edwards

We take Tesla’s Full Self-Driving (Supervised) tech suite for a long drive down the North Island. How did it do?

As one of New Zealand’s first 1400km tests of the Full Self‑Driving (Supervised) from Auckland’s sprawl to Wellington’s tight streets, Tesla’s semi‑autonomous system faced everything from flooded rural roads to city congestion — with a human ready to step in when Kiwi conditions proved a bit much.

Setting off

My Model 3 Long Range had the latest software update and FSD Supervised subscription switched on. I set our first stop for the night — Āpiti in the Tararuas — as the destination, selected Full Self‑Driving, and tapped the brake to confirm. The car took control and immediately turned the wrong way, uncovering what is for now the biggest flaw in the system — carparks.

They aren’t generally mapped, so the car went the wrong way and took a long multi‑point turn to get out of Tesla’s own carpark. I’m not surprised at this. Smart Summon will likely take the work out of parking when it arrives, and Tesla’s system will improve as more customer data accumulates (over one million kilometres were driven in NZ and Australia in less than two weeks of operation). Tesla has already released a US update improving performance where marked roads end and driveways begin, including garage parking.

Leaving Auckland, the system impressed early. It merged confidently, maintained gaps accurately, and stuck to the posted limits within a kilometre or two. A mistake by me briefly killed the system, but a quick tap on the steering wheel reactivated it. It even handled the motorway roadworks near Bombay without flinching, staying perfectly centred between temporary cones.

South of Cambridge, things got more interesting. Low cloud rolled in and rain began. FSD held lane position better than most humans would in low visibility, reading markings through fog and slowing slightly for sharper bends.

It isn’t the fastest car on the road. By law, a self‑driving car can’t speed. You can apply an offset to the limit, but we left it standard, using the accelerator pedal to encourage quicker progress. It also trundles through roadworks at 30 km/h — legal but unpopular — which can earn you a tail of impatient drivers.

Back on the highway, FSD resumed without complaint. The driver‑monitoring camera quickly became the biggest annoyance. Glance at the screen for more than a second, or look down to adjust something, and it starts warning you. Keep it up and it disengages entirely. After 200 kilometres, my neck hurt more from keeping my eyes fixed forward than from the drive itself.

Into the mountains

At Taupō, I stopped to recharge and grab a coffee. Getting out of the supercharger carpark, FSD simply couldn’t map its way through the tight rows and angled exits. I had to drive out manually. It’s a consistent weakness — anything off the official map, like carparks or private drives, confuses it completely.

The next leg toward Āpiti showed more strengths. On open, flat roads it was superb — smooth inputs, consistent lane discipline, clean overtakes. A stiff Manawatū crosswind had the car oscillating slightly within the lane, but the corrections were subtle and predictable.

It even read temporary digital speed signs correctly, slowing from 100 to 80 km/h as required. The problem was getting back up to speed — it waited almost ten seconds after the limit increased before accelerating again.

Climbing through Vinegar Hill toward Kimbolton and Cheltenham, rain and fog returned as darkness fell. While it sometimes took corners a smidge faster than ideal, it never felt unsafe. Despite warnings about “poor GPS location accuracy” and a “camera obscured” alert, it didn’t falter.

On to Wellington

Day two brought clear skies, and the initial leg down from the hills was flawless. For every ten‑second flaw in this story, there were three‑plus hours of perfect driving — keep that in mind.

Approaching Bulls, the system briefly thought the footpath was the best way into the superchargers, steering toward the kerb before I intervened. In fairness, the entrance is confusing. The most concerning moment came in Levin, where, having bypassed the main street, it needed to return to the highway via a level crossing on a steep rise. It climbed to the track’s level then stopped with its nose close enough to be worrying — apparently because the far lane was full.

Close quarters

Wellington brings its own challenges. With a few interested observers on board — including the NZ Transport Agency’s autonomous‑driving specialist — I made multiple laps of the city. Attempts to catch it out on narrow, busy streets mostly failed. It coped with one‑way systems, managed a late but polite lane change for roadworks, and squeezed itself down a tight and twisty Te Aro lane.

It even surprised me with one of the most intelligent moves of the trip: spotting a Land Cruiser driver intent on claiming right of way in a pinch‑point, it reversed uphill and around a corner to create clearance.

Most of the narrow‑street work was slow, again needing a gentle pedal prompt to pick up pace. An approaching cyclist startled it into pausing at a roundabout — not ideal, but “Tesla parks in roundabout” beats “Tesla takes out cyclist.”

Verdict

Across the 1400‑kilometre run — including the return leg — I logged about half a dozen disengagements: one for flooding, one for the rail line, one for the footpath incident, and several minor corrections for carparks and lane choices. Yet for 99 percent of the drive, the car behaved like a calm, precise chauffeur — reading the road, adapting speed, and showing no fatigue.

FSD Supervised isn’t magic. It’s a remarkably capable co‑driver that still depends on a human brain for the unexpected. On long, consistent stretches it’s superb; in complex or unmapped environments, it’s still an advanced student.

The technology feels close. However New Zealand’s geography still has a few lessons to teach Tesla. And learn it will.

Tesla Full Self‑Driving (Supervised)

What it is

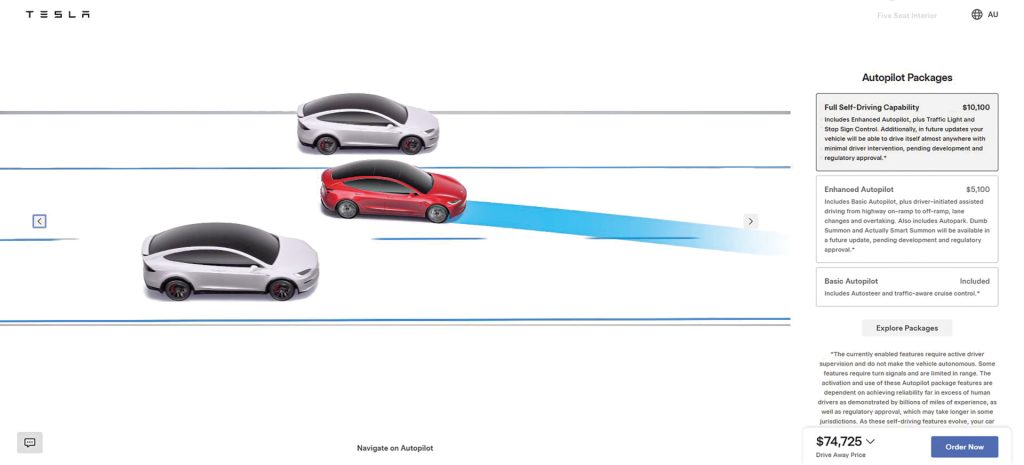

Tesla’s Full Self‑Driving (Supervised), or FSD‑S, is the company’s most advanced driver‑assist system available in New Zealand. It can steer, brake and navigate city streets, intersections, and highways, provided the driver remains attentive.

Currently, Hardware 4 (HW4)

vehicles — including the latest Model 3 Highland and Model Y — support FSD‑S. Indications are that Hardware 3 (HW3) cars may gain access later, though Tesla hasn’t confirmed when.

How it works

FSD‑S relies on Tesla’s camera‑based Vision system, using eight exterior cameras and a cabin camera for driver monitoring. Data is processed by the onboard neural‑network computer, which interprets lanes, vehicles, and objects to control steering, throttle, and braking. Drivers can gently guide the car using indicators or the accelerator without disengaging FSD — a useful feature that makes the system feel cooperative rather than rigid.

FSD‑S isn’t fully autonomous. The driver must stay alert and be ready to intervene at any time; the system disengages if attention warnings are ignored.

FSD‑S launched widely in North America in 2023 and reached Australia and New Zealand in 2025 via over‑the‑air updates. Tesla continues to refine it using anonymised fleet data collected from real‑world driving.